Locating the Tragedy of Darjeeling Tea

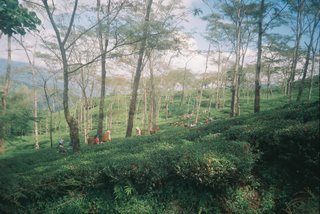

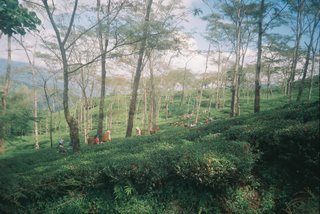

Among the teas cultivated in India, the most celebrated one comes from Darjeeling Hills. The best of India's prize Darjeeling Tea is considered the world's finest tea. The region has been cultivating, growing and producing tea for the last 150 years. The complex and unique combination of geo-environmental and agro-climatic conditions characterising the region lends to the tea grown in the area a distinct quality and flavour that has won the patronage and recognition all over the world for the last 1.5 century. The tea produced in the region and having special characteristics has for long been known across the globe as ‘Darjeeling Tea’.

The then superintendent of Darjeeling, Dr. Campbell and Major Crommelin are said to have first introduced tea in Darjeeling during 1840-50 on experimental basis out of the seeds imported from China. According to records, the first commercial tea gardens were planted in 1852. Darjeeling was then a very sparsely populated region and was only used as a hill resort. Tea being a labour intensive industry needed sufficient number of workers to plant, tend, pluck and finally manufacture the produce. Hence, the people from the neighbouring regions mainly Nepal were encouraged to immigrate and engage as labourers in the tea gardens. It appears that by the year 1866, Darjeeling had 39 gardens producing a total crop of 21,000 kilograms of tea. In 1870, the number of gardens increased to 56 to produce about 71,000 kgs of tea harvested from 4,400 hectares. By 1874, tea cultivation in Darjeeling was found to be a profitable venture and there were 113 gardens with approximately 6000 hectares. Today there are 87 registered gardens sprawled across the geographical area of 20,200 hectares.

Darjeeling Tea Industry in Crisis

In the context of the widespread crisis in tea gardens located across the geographies of the country Darjeeling Hills has not been an exception. There has been frequent reporting on the leading news dailies mainly that tea gardens in Darjeeling Hills suffer from more than one problem. Sickness, closure/lock up, abandonment of the tea gardens; wage, education, health and livelihood issues of the workers, issues with respect to the crop productivity, frequent violence and strikes across tea gardens, issues of intellectual property rights under WTO regime, falling value of Darjeeling Tea in the global market and competition from the teas coming from Nepal, Sri Lanka, African countries etc. are some of the major problems faced by Darjeeling Tea Industry in recent times.

The total production of tea in Darjeeling hills has varied between 8-11 million kilograms in the last one decade or so. A major part of the annual production of Darjeeling tea is exported. The key buyers of Darjeeling tea are Germany, Japan, UK, USA, and other EU countries. In the year 2000 about 8.5 million kgs of Darjeeling tea was exported, amounting to a total value of USD 30 million. There has been a continuous decline in the total production of tea and per hectare yield of Darjeeling Tea in the last 50 years. There was a time during 1960s and 1970s when Darjeeling Himalaya used to produce over 15 million kgs of tea. This figure went down during the 1990s. The decline has been drastic since the mid 1990s. Today the region produces less than 9 million kgs of tea. One of the main reasons of the falling production is attributed to the declining yield of tea leaves in the area. The Darjeeling tea industry roughly generates about Rs. 150-200 crores annually. However, none of the tea estates in Darjeeling has made public the exact figure of its annual earning so far. Tea companies have always remained silent in this connection and thus have kept the workers in dark over the years. There have been plenty of rumours that the price of Darjeeling Tea has been falling down in the global market in recent times due to competitions from the countries like Kenya, Sri Lanka, Nepal, Japan and South East Asian Countries.

Factors responsible for the present status of Darjeeling Tea

The over all health of the tea gardens in Darjeeling Hills and the associated socio-economic conditions of the resident tea garden labourers therein cannot be attributed to a single factor. A series of factors and counter factors have played their interlinked roles over the years in this connection. Some of the major contributing factors that have acted and reacted and ultimately paved the way to the present situation of Darjeeling tea, tea gardens and the garden labourers may be briefly listed below. There is a need to debate, discuss and conduct a more systematic research on these factors often historic in nature in order to understand the crux of the problems characterising Darjeeling tea and the garden workers and address the same in the near future.

Globalisation and Liberalisation

In a liberalised world market almost 40 million kg is sold as ‘Darjeeling Tea’ although the total production of Darjeeling tea is less than 10 million kg. Most of these teas come from Sri Lanka and Kenya. Some of the fake tea is called Lanka Darjeeling or Hamburg Darjeeling but most of the time it is called Pure Darjeeling. Further, Japan, a largely orthodox-tea growing area, has already discovered the chemical constituents present in the Darjeeling variety, although industry watchers say that this will not enable them to grow the true Darjeeling variety. Such situation has led to the degradation of international reputation of Darjeeling Tea in recent times. There have been cases when pure Darjeeling Tea has not found its place in the international market for fear of fake supply. This has surely impacted the Tea Gardens and Tea Garden Workers in the region.

In an effort to stop this market and sustain it Intellectual Property Rights the Darjeeling logo was created as early as in 1986 and registered in U.K., U.S.A., Canada, Japan, Egypt and under Madrid, covering eight countries. Further a Certification Trade Mark Scheme for Darjeeling Tea was launched in 2000 in view of several complaints coming from across the world with regard to fake Darjeeling Tea supplied in the international market and its long term impact back home. However, Darjeeling tea is still not recognised by WTO as a Geographical Indicator. Article 23 of TRIPS gives protection to Wines and Spirits currently but not for other products .

In the mean time we have no other options but to protect Darjeeling tea through Darjeeling logo and Certification Mark. We, however, need to keep on debating on the protection of Darjeeling Tea in the liberalised global market and seek to negotiate its place in the WTO meetings. The point is not only to protect Darjeeling tea but the workers that are engaged in its production as well.

Age of the Tea Bushes

One of the prime concerns of Darjeeling tea is that majority of the tea bushes in Darjeeling hills have well passed their prime age. About 66 percent of the total tea bushes are over 50 years of age while more that 50% have been there for over 100 years now. Over 16 percent of the bushes are between 20-50 years of age while only about 20 percent are under the age of 20 years. Further, there are tea bushes that are over 140 years old. According to the recent study conducted by the Tea Board of India, only 8 percent of the old tea bushes have been uprooted and replanted. This has seriously impacted the productivity of the tea gardens and the annual production has gone down from over 14 million kilogram in the 1960s to less than 10 million kilograms in recent times. The yield of Darjeeling Tea, in recent times, is below 550 kg per hectare far below the national average of over 1750 kg per hectare.

Consultation with the labourers, tea experts and trade union leaders bring forth the following measures that the Tea Companies/Governments need to take in the near future to save Darjeeling Tea and the socio-economic health of garden workers.

· All the old tea bushes need to be uprooted in the phased manner and re-plantation needs to be carried out accordingly,

· All the tea gardens need to practice bio-organic farming in the long run so as to attract the buyers with a healthy, chemical free Darjeeling tea. This is also important in view of safe guarding the health of the workers, their family members, regional environment and the prevailing sanitary and phyto-sanitary standards under WTO.

· Promote and encourage the ‘Small Organic Tea Growers’ across the villages in order to supplement the falling production of tea and generate sustainable income among the garden workers.

Mention should be made that there have been repeated suggestions from the trade unions, researchers, tea experts, Tea Board of India and others to replant the old tea bushes in Darjeeling Hill. However, tea companies have over the years turned deaf ear to this grave issue for fear of losing their profit. Re-plantation of tea bushes is a tedious job. Further, once an old tea bush is replanted it takes at least 5 years to reach a stage when green tea leaves can be plucked. It is this gap of 5 years that the tea companies fear most, as they do not get money for a period of five years but have to pay their workers and invest huge amount in the re-plantation venture.

The Issue of multiplication

The problem of ‘multiplication’ is observed to be a serious concern across all the tea gardens located in Darjeeling Hills. The term multiplication refers to the ever increasing number of population in tea gardens. As noted earlier, workers across the tea gardens are majorly migrant labourers from Nepal. Initially, they were encouraged by the British to come over to the area in order to bring to term the virgin forested lands often steep in nature and physically challenging. However, at later years there were lots of push factors from Nepal and pull factors from their Indian counter parts. Hence, over the years the population across the tea estates grew geometrically. One of the major concerns with respect to increasing chaos across the tea gardens is that there has been no provision to send back the retired labourers from the gardens and those households that are not working in the garden. On the other hand, the area under tea gardens has, however, remained constant or increased very gradually over the years. The management has little or no interest to provide alternative livelihood strategies to over 60 percent of the population who do not work in the tea gardens but only reside there. The growing population across the tea gardens in Darjeeling Hills has inflicted a tremendous pressure on the society, economy and rural ecology in the region.

Monoculture and Exhaustion of Soil Nutrients

Another important issue that has directly affected the production and yield of tea leaves and has a bearing in one or the way on the overall socio-economic health of the workers of the gardens has been the monoculture and the subsequent exhaustion of soil nutrients. Tea experts believe the soils in plantation areas are depleted of nutrients and we cannot have healthy tea bushes on sick soil. This is the result of the monoculture of tea plantations over a considerably longer period of time of over 100 years. Monoculture has also seriously affected the bio-diversity of Darjeeling Hills. It has progressively weakened the genetic strength of tea bushes and other associated plants. The complexity of raising yield essentially lies in the soil. All plantation soils are depleted of minerals and nutrients. Re-mineralisation is not easy or very expensive either but it requires scientific approach.

Impact of Gorkhaland Agitation

The historic movement unleashed by the Nepali speaking inhabitants of Darjeeling Hills under the leadership of Subash Ghising for the separate state of Gorkhaland shook the state of West Bengal in the 1980s. The present socio-economic situations across the tea plantations and other spaces of Darjeeling have many bearings of Gorkhaland Agitation. The impact of Gorkhaland Agitation in the context of the tea gardens and the socio-economic health of the garden labourers can be debated at two levels. First, all the tea gardens hitherto functioning normally were negatively impacted by the agitation often violent in nature. There were copious instances when the top management officials, managers of the garden/estate, owners of the tea gardens fled away from the place never to return back. As a result, management of the tea gardens in Darjeeling severely suffered, so much so that, it could never achieve its pre-agitation level. Worse was the case with gardens owned by the state or central government agencies.

Secondly, the impact of agitation on work culture of the garden labourers has been tremendous. Although this part of the story has never been brought to book it becomes pertinent to debate on this issue in order to understand the crux of the present socio-economic conditions of the garden labourers in the region. Traditionally, garden labourers have been known for their hard work, punctuality, sincerity, work efficiency and respect for the management principles. The Gorkha Land Agitation severely eroded such culture and gave way to the culture of violence and disrespect to the management among the labourers. There are ample instances when the labourers have sought violence, thrashed the managers, and not adhered to the principle of the management in the region in post agitation period. Today a typical garden labour would not hesitate to enter the manager’s chamber and thrash him black and blue if he is dissatisfied with the workings of management instead of settling his grievance through legal channel.

Darjeeling Gorkha Hill Council has been the director and guardian of development initiatives in Darjeeling Hills since its establishment in July 1988. Ironically, however, out of the three important Ts , for which Darjeeling is famous for, Tea and Timber (forest) are not under the direct control of DGHC thus leaving only Tourism under its fold. In case of forest, management of protected forests and un-classed forests are within the executive power of DGHC while reserved forest is under the direct control of the forest department of the state. With regard to tea, tea estates are majorly controlled by private companies under the umbrella of the government and few are under the direct control of the state and central government agencies. Such situation leaves DGHC with very little or no scope to play role in monitoring and directing the functioning and management of the tea gardens.

The plantation Labour Act, 1951

The Plantation Labour Act, 1951 is a Central Government Act. It was formulated with a view to improve the living and working conditions of the workers and the associated people across the gardens. The preamble to this Act aims at providing for the welfare of labour and regulating the conditions of work in plantations. The Government of West Bengal framed rules in 1956 to implement the provisions of this Act. This Act, however, is featured with several pitfalls. Empirical evidences highlight the fact that most of the provisions under the act are virtually violated and flouted by the management and there is no room to punish the culprit. For instance, only the permanent workers (that constitute less than 30 percent of the population of the garden) are privileged to avail the benefits like housing, drinking water, children’s education, health facilities, subsidised ration, clothing, PF and such other benefits as per the Plantation Act. However, the gardens have very little or no provisions for drinking water facilities, housing, latrines, medical provisions, electricity and education even to the permanent workers not to talk of the casuals. Further, as per the Act the management must built a permanent house for 8 percent of the permanent workers every year and gradually sort out the housing problem. Most of the tea gardens are still, however, faced with severe housing problem where labourers live in kutcha and semi-pucca houses with zero sanitary facilities. The Act, moreover, needs a through revision in the context of new market complexities and emerging socio-political behaviour. According to the labour commissioner, Darjeeling, this act has become outdated and does not do any needful to the welfare of garden labourers. There are many temporal issues that the Act carries with it and that have not been corrected across the spectrum of time.

The colonial set up

Tea Gardens, and for that matter all the plantations, still operate in the context of old colonial relationship of masters and the slaves. The basic philosophy is to control the market and totally squeeze the primary producer. As indicated earlier, a feature of the early development of tea plantation system of Darjeeling was the importation of the labour force from outside the region. This imported labour force was settled on plantation lands and permanency of employment was almost by definition. The spaces in the plantation were meticulously charted by a hierarchy of master – subject personages. Such set up ensured that the socio-economic needs of the resident garden society were the responsibility of the plantation systems. Moreover, 80 percent of the garden managers are constituted by the outsiders and all the garden owners are outsiders. Such process strengthened the master slave relationship over the years. The master–slave relationship with the passage of time developed a dependent mind-set into the psyche of the resident garden labourers. Workers across the tea gardens began to increasingly depend on the management for everything. They would get their salary every Friday irrespective of how they performed. Moreover, tea managements on their part never introduced any alternative livelihood strategies to the garden labourers in order to cope with the possible livelihood threats inflicted by various internal and external forces in future times. As a result, with the gradual onset of globalisation & liberalisation and the accompanying market challenges and other associated forces, garden labourers were the major sufferers while the owners of tea companies and their top officials secretly by-passed the negative impacts on labourers through manipulations. Hence, tea gardens closed/abandoned, companies abandoned and the socio-economic situations of the garden labourers went down from bad to worse but the owners and upper level officials never suffered; they were rich and are still rich.

With the consequent sickness and closure/abandonment of the gardens the dependency cushion that the plantation system provided them all these years was suddenly withdrawn. For the first time in their lives, the resident garden workers were left to fend for themselves. They were ill prepared to face the new situation in with they were thrown into. It demanded an independent decision making mind-set and newer skills that would allow them to take control of their destiny. Unfortunately their mind-set were still in a dependency mode and this created havoc with their way of life, creating massive socio-economic problems in all walks of life and famine swept through many of the tea garden societies .

**Shorter version of this article was published in The Statesman, March 11, 2006

Among the teas cultivated in India, the most celebrated one comes from Darjeeling Hills. The best of India's prize Darjeeling Tea is considered the world's finest tea. The region has been cultivating, growing and producing tea for the last 150 years. The complex and unique combination of geo-environmental and agro-climatic conditions characterising the region lends to the tea grown in the area a distinct quality and flavour that has won the patronage and recognition all over the world for the last 1.5 century. The tea produced in the region and having special characteristics has for long been known across the globe as ‘Darjeeling Tea’.

The then superintendent of Darjeeling, Dr. Campbell and Major Crommelin are said to have first introduced tea in Darjeeling during 1840-50 on experimental basis out of the seeds imported from China. According to records, the first commercial tea gardens were planted in 1852. Darjeeling was then a very sparsely populated region and was only used as a hill resort. Tea being a labour intensive industry needed sufficient number of workers to plant, tend, pluck and finally manufacture the produce. Hence, the people from the neighbouring regions mainly Nepal were encouraged to immigrate and engage as labourers in the tea gardens. It appears that by the year 1866, Darjeeling had 39 gardens producing a total crop of 21,000 kilograms of tea. In 1870, the number of gardens increased to 56 to produce about 71,000 kgs of tea harvested from 4,400 hectares. By 1874, tea cultivation in Darjeeling was found to be a profitable venture and there were 113 gardens with approximately 6000 hectares. Today there are 87 registered gardens sprawled across the geographical area of 20,200 hectares.

Darjeeling Tea Industry in Crisis

In the context of the widespread crisis in tea gardens located across the geographies of the country Darjeeling Hills has not been an exception. There has been frequent reporting on the leading news dailies mainly that tea gardens in Darjeeling Hills suffer from more than one problem. Sickness, closure/lock up, abandonment of the tea gardens; wage, education, health and livelihood issues of the workers, issues with respect to the crop productivity, frequent violence and strikes across tea gardens, issues of intellectual property rights under WTO regime, falling value of Darjeeling Tea in the global market and competition from the teas coming from Nepal, Sri Lanka, African countries etc. are some of the major problems faced by Darjeeling Tea Industry in recent times.

The total production of tea in Darjeeling hills has varied between 8-11 million kilograms in the last one decade or so. A major part of the annual production of Darjeeling tea is exported. The key buyers of Darjeeling tea are Germany, Japan, UK, USA, and other EU countries. In the year 2000 about 8.5 million kgs of Darjeeling tea was exported, amounting to a total value of USD 30 million. There has been a continuous decline in the total production of tea and per hectare yield of Darjeeling Tea in the last 50 years. There was a time during 1960s and 1970s when Darjeeling Himalaya used to produce over 15 million kgs of tea. This figure went down during the 1990s. The decline has been drastic since the mid 1990s. Today the region produces less than 9 million kgs of tea. One of the main reasons of the falling production is attributed to the declining yield of tea leaves in the area. The Darjeeling tea industry roughly generates about Rs. 150-200 crores annually. However, none of the tea estates in Darjeeling has made public the exact figure of its annual earning so far. Tea companies have always remained silent in this connection and thus have kept the workers in dark over the years. There have been plenty of rumours that the price of Darjeeling Tea has been falling down in the global market in recent times due to competitions from the countries like Kenya, Sri Lanka, Nepal, Japan and South East Asian Countries.

Factors responsible for the present status of Darjeeling Tea

The over all health of the tea gardens in Darjeeling Hills and the associated socio-economic conditions of the resident tea garden labourers therein cannot be attributed to a single factor. A series of factors and counter factors have played their interlinked roles over the years in this connection. Some of the major contributing factors that have acted and reacted and ultimately paved the way to the present situation of Darjeeling tea, tea gardens and the garden labourers may be briefly listed below. There is a need to debate, discuss and conduct a more systematic research on these factors often historic in nature in order to understand the crux of the problems characterising Darjeeling tea and the garden workers and address the same in the near future.

Globalisation and Liberalisation

In a liberalised world market almost 40 million kg is sold as ‘Darjeeling Tea’ although the total production of Darjeeling tea is less than 10 million kg. Most of these teas come from Sri Lanka and Kenya. Some of the fake tea is called Lanka Darjeeling or Hamburg Darjeeling but most of the time it is called Pure Darjeeling. Further, Japan, a largely orthodox-tea growing area, has already discovered the chemical constituents present in the Darjeeling variety, although industry watchers say that this will not enable them to grow the true Darjeeling variety. Such situation has led to the degradation of international reputation of Darjeeling Tea in recent times. There have been cases when pure Darjeeling Tea has not found its place in the international market for fear of fake supply. This has surely impacted the Tea Gardens and Tea Garden Workers in the region.

In an effort to stop this market and sustain it Intellectual Property Rights the Darjeeling logo was created as early as in 1986 and registered in U.K., U.S.A., Canada, Japan, Egypt and under Madrid, covering eight countries. Further a Certification Trade Mark Scheme for Darjeeling Tea was launched in 2000 in view of several complaints coming from across the world with regard to fake Darjeeling Tea supplied in the international market and its long term impact back home. However, Darjeeling tea is still not recognised by WTO as a Geographical Indicator. Article 23 of TRIPS gives protection to Wines and Spirits currently but not for other products .

In the mean time we have no other options but to protect Darjeeling tea through Darjeeling logo and Certification Mark. We, however, need to keep on debating on the protection of Darjeeling Tea in the liberalised global market and seek to negotiate its place in the WTO meetings. The point is not only to protect Darjeeling tea but the workers that are engaged in its production as well.

Age of the Tea Bushes

One of the prime concerns of Darjeeling tea is that majority of the tea bushes in Darjeeling hills have well passed their prime age. About 66 percent of the total tea bushes are over 50 years of age while more that 50% have been there for over 100 years now. Over 16 percent of the bushes are between 20-50 years of age while only about 20 percent are under the age of 20 years. Further, there are tea bushes that are over 140 years old. According to the recent study conducted by the Tea Board of India, only 8 percent of the old tea bushes have been uprooted and replanted. This has seriously impacted the productivity of the tea gardens and the annual production has gone down from over 14 million kilogram in the 1960s to less than 10 million kilograms in recent times. The yield of Darjeeling Tea, in recent times, is below 550 kg per hectare far below the national average of over 1750 kg per hectare.

Consultation with the labourers, tea experts and trade union leaders bring forth the following measures that the Tea Companies/Governments need to take in the near future to save Darjeeling Tea and the socio-economic health of garden workers.

· All the old tea bushes need to be uprooted in the phased manner and re-plantation needs to be carried out accordingly,

· All the tea gardens need to practice bio-organic farming in the long run so as to attract the buyers with a healthy, chemical free Darjeeling tea. This is also important in view of safe guarding the health of the workers, their family members, regional environment and the prevailing sanitary and phyto-sanitary standards under WTO.

· Promote and encourage the ‘Small Organic Tea Growers’ across the villages in order to supplement the falling production of tea and generate sustainable income among the garden workers.

Mention should be made that there have been repeated suggestions from the trade unions, researchers, tea experts, Tea Board of India and others to replant the old tea bushes in Darjeeling Hill. However, tea companies have over the years turned deaf ear to this grave issue for fear of losing their profit. Re-plantation of tea bushes is a tedious job. Further, once an old tea bush is replanted it takes at least 5 years to reach a stage when green tea leaves can be plucked. It is this gap of 5 years that the tea companies fear most, as they do not get money for a period of five years but have to pay their workers and invest huge amount in the re-plantation venture.

The Issue of multiplication

The problem of ‘multiplication’ is observed to be a serious concern across all the tea gardens located in Darjeeling Hills. The term multiplication refers to the ever increasing number of population in tea gardens. As noted earlier, workers across the tea gardens are majorly migrant labourers from Nepal. Initially, they were encouraged by the British to come over to the area in order to bring to term the virgin forested lands often steep in nature and physically challenging. However, at later years there were lots of push factors from Nepal and pull factors from their Indian counter parts. Hence, over the years the population across the tea estates grew geometrically. One of the major concerns with respect to increasing chaos across the tea gardens is that there has been no provision to send back the retired labourers from the gardens and those households that are not working in the garden. On the other hand, the area under tea gardens has, however, remained constant or increased very gradually over the years. The management has little or no interest to provide alternative livelihood strategies to over 60 percent of the population who do not work in the tea gardens but only reside there. The growing population across the tea gardens in Darjeeling Hills has inflicted a tremendous pressure on the society, economy and rural ecology in the region.

Monoculture and Exhaustion of Soil Nutrients

Another important issue that has directly affected the production and yield of tea leaves and has a bearing in one or the way on the overall socio-economic health of the workers of the gardens has been the monoculture and the subsequent exhaustion of soil nutrients. Tea experts believe the soils in plantation areas are depleted of nutrients and we cannot have healthy tea bushes on sick soil. This is the result of the monoculture of tea plantations over a considerably longer period of time of over 100 years. Monoculture has also seriously affected the bio-diversity of Darjeeling Hills. It has progressively weakened the genetic strength of tea bushes and other associated plants. The complexity of raising yield essentially lies in the soil. All plantation soils are depleted of minerals and nutrients. Re-mineralisation is not easy or very expensive either but it requires scientific approach.

Impact of Gorkhaland Agitation

The historic movement unleashed by the Nepali speaking inhabitants of Darjeeling Hills under the leadership of Subash Ghising for the separate state of Gorkhaland shook the state of West Bengal in the 1980s. The present socio-economic situations across the tea plantations and other spaces of Darjeeling have many bearings of Gorkhaland Agitation. The impact of Gorkhaland Agitation in the context of the tea gardens and the socio-economic health of the garden labourers can be debated at two levels. First, all the tea gardens hitherto functioning normally were negatively impacted by the agitation often violent in nature. There were copious instances when the top management officials, managers of the garden/estate, owners of the tea gardens fled away from the place never to return back. As a result, management of the tea gardens in Darjeeling severely suffered, so much so that, it could never achieve its pre-agitation level. Worse was the case with gardens owned by the state or central government agencies.

Secondly, the impact of agitation on work culture of the garden labourers has been tremendous. Although this part of the story has never been brought to book it becomes pertinent to debate on this issue in order to understand the crux of the present socio-economic conditions of the garden labourers in the region. Traditionally, garden labourers have been known for their hard work, punctuality, sincerity, work efficiency and respect for the management principles. The Gorkha Land Agitation severely eroded such culture and gave way to the culture of violence and disrespect to the management among the labourers. There are ample instances when the labourers have sought violence, thrashed the managers, and not adhered to the principle of the management in the region in post agitation period. Today a typical garden labour would not hesitate to enter the manager’s chamber and thrash him black and blue if he is dissatisfied with the workings of management instead of settling his grievance through legal channel.

Darjeeling Gorkha Hill Council has been the director and guardian of development initiatives in Darjeeling Hills since its establishment in July 1988. Ironically, however, out of the three important Ts , for which Darjeeling is famous for, Tea and Timber (forest) are not under the direct control of DGHC thus leaving only Tourism under its fold. In case of forest, management of protected forests and un-classed forests are within the executive power of DGHC while reserved forest is under the direct control of the forest department of the state. With regard to tea, tea estates are majorly controlled by private companies under the umbrella of the government and few are under the direct control of the state and central government agencies. Such situation leaves DGHC with very little or no scope to play role in monitoring and directing the functioning and management of the tea gardens.

The plantation Labour Act, 1951

The Plantation Labour Act, 1951 is a Central Government Act. It was formulated with a view to improve the living and working conditions of the workers and the associated people across the gardens. The preamble to this Act aims at providing for the welfare of labour and regulating the conditions of work in plantations. The Government of West Bengal framed rules in 1956 to implement the provisions of this Act. This Act, however, is featured with several pitfalls. Empirical evidences highlight the fact that most of the provisions under the act are virtually violated and flouted by the management and there is no room to punish the culprit. For instance, only the permanent workers (that constitute less than 30 percent of the population of the garden) are privileged to avail the benefits like housing, drinking water, children’s education, health facilities, subsidised ration, clothing, PF and such other benefits as per the Plantation Act. However, the gardens have very little or no provisions for drinking water facilities, housing, latrines, medical provisions, electricity and education even to the permanent workers not to talk of the casuals. Further, as per the Act the management must built a permanent house for 8 percent of the permanent workers every year and gradually sort out the housing problem. Most of the tea gardens are still, however, faced with severe housing problem where labourers live in kutcha and semi-pucca houses with zero sanitary facilities. The Act, moreover, needs a through revision in the context of new market complexities and emerging socio-political behaviour. According to the labour commissioner, Darjeeling, this act has become outdated and does not do any needful to the welfare of garden labourers. There are many temporal issues that the Act carries with it and that have not been corrected across the spectrum of time.

The colonial set up

Tea Gardens, and for that matter all the plantations, still operate in the context of old colonial relationship of masters and the slaves. The basic philosophy is to control the market and totally squeeze the primary producer. As indicated earlier, a feature of the early development of tea plantation system of Darjeeling was the importation of the labour force from outside the region. This imported labour force was settled on plantation lands and permanency of employment was almost by definition. The spaces in the plantation were meticulously charted by a hierarchy of master – subject personages. Such set up ensured that the socio-economic needs of the resident garden society were the responsibility of the plantation systems. Moreover, 80 percent of the garden managers are constituted by the outsiders and all the garden owners are outsiders. Such process strengthened the master slave relationship over the years. The master–slave relationship with the passage of time developed a dependent mind-set into the psyche of the resident garden labourers. Workers across the tea gardens began to increasingly depend on the management for everything. They would get their salary every Friday irrespective of how they performed. Moreover, tea managements on their part never introduced any alternative livelihood strategies to the garden labourers in order to cope with the possible livelihood threats inflicted by various internal and external forces in future times. As a result, with the gradual onset of globalisation & liberalisation and the accompanying market challenges and other associated forces, garden labourers were the major sufferers while the owners of tea companies and their top officials secretly by-passed the negative impacts on labourers through manipulations. Hence, tea gardens closed/abandoned, companies abandoned and the socio-economic situations of the garden labourers went down from bad to worse but the owners and upper level officials never suffered; they were rich and are still rich.

With the consequent sickness and closure/abandonment of the gardens the dependency cushion that the plantation system provided them all these years was suddenly withdrawn. For the first time in their lives, the resident garden workers were left to fend for themselves. They were ill prepared to face the new situation in with they were thrown into. It demanded an independent decision making mind-set and newer skills that would allow them to take control of their destiny. Unfortunately their mind-set were still in a dependency mode and this created havoc with their way of life, creating massive socio-economic problems in all walks of life and famine swept through many of the tea garden societies .

**Shorter version of this article was published in The Statesman, March 11, 2006

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home