Development of Education in Sikkim: Himalayan Example

It is often argued that education is one of the most important indicators of socio-cultural and economic development. Prior to the advent of the skills of reading and writing the society could be classified as being in the pre-literate stage. The change from preliterate to literate society is said to have begun somewhere during the fourth millennium BC through a gradual transition from pictography to the use of an alphabet. After the advent of the dual skills of reading and writing the relevance of literacy and education to the cultural advancement enhanced significantly.

Today education is the single most important means of judging the levels of human development in a particular region or at an individual level. Education is essential for eradicating poverty, free play of demographic process, and overall human development. On the other hand, lack of education, wisdom and illiteracy leads to low dignity, ignorance and poverty, mental isolation and hampers socio-economic and political maturity. Moreover, education influences other important attributes of human development like fertility, mortality, mobility, occupancy etc. More importantly, it is a critical instrument for bringing about social, economic and political inclusion and a durable integration of people, particularly those excluded from the mainstream of any society (NHDR: 2001, 2002). The process of educational attainment hence has an impact on all aspects of life and is the best social investment in view of the synergies and the positive externalities that it generates for the people in their well being.

Education in Sikkim in the Context of Geo-Environmental and historical ConstraintsSikkim, a small Himalayan kingdom till 1975, land locked by Nepal in the west, Tibet in the north, Bhutan in the northeast and Darjeeling in the south had been a relatively close entity within the Indian subcontinent. The geographical location and the environmental set up in the region further have accentuated the problem in this regard. The scattered tribal settlements across the uneven geography of the region, climatic constraints and limited amount of horizontal interaction historically hindered the penetration of formal education system in the region. Even during the first half of the 20th century when education was the single most important aspect of development paradigm formal education did not make any remarkable headway in the state.

Further, the earlier Sikkimese rulers could hardly think of the importance of the formal and scientific education system and majorly engaged in the traditional political activities. As a consequence, while the neighbouring hills of Darjeeling, which was historically, a part of the Kingdom of Sikkim, was steadily advancing as a result of the introduction of various formal English education institutions under British India Sikkim silently lagged behind educationally and for that matter economically, socially and politically. The inability of the monarch to recognize the role of scientific education in the advancement of human development cost the region dearly at the later period of time.

History of Education and Educational Institutions in Sikkim Although we have noted the geographical and historical constraints that prevented the advent of formal education system in Sikkim it would, however, be wrong to maintain that there wasn’t any education system in Sikkim per se. There were various modes of traditional education patterns prevalent at different periods in the history of Sikkim.

Traditional education systems of Sikkim were very life centered, practical and experience based. Lama (2001), in this connection, rightly invokes the famous traditional Nepali saying ‘ pari guni ke kam, haolo joti khayo mam’ meaning thereby, what is the use of reading and writing as ultimately you have to plough the field for your sustenance. Such folk saying among the Nepalis in Darjeeling and Sikkim hills reflect their levels of thinking and degree of wisdom during good old days. Growing children, till attainment of adolescence obtained hands on knowledge of things, ceremonies and functions. The family was the focal point of nearly all-educational endeavors with a key role being played by women.

Education in Sikkim for most of the nineteenth century was of the monastic type. Buddhist literature was read both at home and in the monastic schools. They imparted religious education for the preparation of young monks to priesthood. The schools in Tashiding, Thulung, Pemayongtse and Sangnachaling monastries were famous as centres of monastic education in those days (Jangira, 1977 as quoted in Lama, 2001).

The genesis of the monastic schools could be traced back to the arrival of Buddhism in Sikkim sometimes in the 16th Century AD. Famous scholars like Shanta Rakshita and Guru Padma, who consecrated the first ruler of Sikkim in Yuksum and also got the support of temporal power as well. Even today the Ecclesiastical Department in the Government of Sikkim has recorded 163 monastries and temples all over Sikkim excluding the small shrine (Lama, 2001). Monastries and temples have made a significant contribution to the education in Sikkim. Buddhist literature, especially the Mahayana and Tantric texts were available in Tibetan and had been the medium of instruction. The fundamental Buddhist teaching and chanting of some important prayers included in religious books formed the curriculum of monastic education. The curriculum also included the study of diversified subjects such as painting, sculpture, astrology, mathematics, medicine, philosophy, literature, tantra and so on (Lama, 2001). The Shedas (Monastic Colleges for Higher Studies in Buddhist Literature) at Deorali and Rumtek are primarily aimed at reviving the formal educational role of the monastries.

By the late nineteenth century, there was the gradual advent of the Christian Missionary Education in Sikkim with some support from the landlords/Kazis. The Maharaja of Sikkim did not, however, favour the Christian Missionary activity. The missionaries were not allowed to live in Gangtok. In 1924, Mary Scott was for the first time allowed to open a school for girls in Gangtok, the first matriculation class of which passed out the examination (with four candidates) in 1945. The school continued to grow and became a recognized higher secondary school in 1961. One of the main features of the Missionary schools for girls was the industrial teaching mainly sewing and knitting. Besides, vocational training was also a part of the curriculum. In fact, for many years until the beginning of the twentieth century primary schools set up by the church offered the only means of basic education (Lama, 2001).

The first government school to be established in Sikkim was the Bhutia Boarding School (1906). In 1907, the second government school namely, Nepali Boarding School was started in the present day Lal Bazar area. The government amalgamated the Bhutia and Nepali Boarding Schools into what it is known today as the Sir Tashi Namgyal Academy in the year 1924. Sikkim as of 1920 had only 21 schools out of which 6 were government schools, 13 missionary schools and 2 of the schools were under the landlords. The number of schools continued to increase over the years and by 1961 i.e. by the end of the First Five Year Plan period the number of schools in Sikkim had risen to 182 registering an increase of 107 percent as the number in 1954 when there were only 88 schools.

Following the merger of Sikkim in the Indian Union in year 1975 the state got tremendous momentum in its educational status in terms of the total number of schools, number of teachers and quality of education. Hence, as of 2002 Sikkim had under its fold about 2000 schools, over 10000 teachers and almost had attained 70 percent of literacy rate. Thus, there is no doubt that the state of Sikkim has done tremendous job in the last 30 years and it is hoped similar momentum would be followed by the state in the future.

Teacher Recruitment Policy in Sikkim: Issues of Son of the Soil PolicySikkim follows a son of the soil policy in recruiting the servants for the service of the state in all the departments of the state including education. Such precedence has found place in the state following massive in migration of the outsiders and perceived threat to the loss of the sources of livelihoods of the ethnic communities in the state.

For the recruitment of the teachers advertisements are brought out in the state gazetteer from time to time. Only the Sikkimese subjects are recruited in the educational institutes on a regular basis. Under the exceptional cases in that if the subjects of Sikkim do not possess the required qualification for a particular posts, like post graduate teachers particularly in science stream, faculties in colleges or technical institutes, outsiders are considers but mainly under contract basis.

Such policy in the state has impacted the society and economy both positively and negatively. On the positive side, the state through its son of the soil policy has been, to some extent, successful in reserving jobs to the ethnic Sikkimese and check the in migration and subsequent piracy of the jobs in the state. On the other hand, however, the son of the soil policy of the state has led to the retardation of the Sikkimese economy and society. 100 per cent reservation of jobs to the state subjects has impacted the efficiency and effectiveness on the part of the servants in all the sectors of the economy including education. In the era when we are talking of global network, unhindered horizontal exchange of goods and knowledge, dynamic and vibrant economy Sikkim cannot afford to check the horizontal mobility across its boarder. If Sikkim can invite and encourage the global investments why can’t it promote and support global talents- in the form of dynamic development managers, efficient and quality teachers, trained development professionals and development planners, engineers and architects- in a controlled manner. The time has come to open up and encourage the global talents to make Sikkimese economy vibrant and Sikkimese society dynamic.

Teachers TrainingOf late the state of Sikkim has been strongly committed to quality education. Efforts are being made for improving the quality of teachers through various teachers training programmes.

In this connection, the District Institute of Education and Training (DIET), Gangtok, has been playing pioneering role. It has been promoting in service training programme of one year to primary teachers and headmasters of primary teachers for both government and private schools. In addition DIET in collaboration with the education department of the state has been conducting training and orientation programmes to the language teachers including Nepali, Bhutia, Lepcha and limbo with the latest techniques in handling the language curriculum.

Further, the department of education has sought training programme for primary and secondary level teachers with the help of IGNOU in a phased manner. While primary level teachers undergo IGNOU’s specially designed six months course called Certificate in Primary Education (CPE), secondary level teachers undergo the university’s normal tow years B.Ed course. For the smooth running of the programme 10 study centres all over the state for CPE and three centres for B.Ed programmes has been activated.

Besides, there are three private TTIs located in south and east districts that impart training to the qualified persons both in service and out side service. These institutes are also open to the candidates from outside the Sikkim.

Higher and Technical/Professional Education in SikkimThe state of Sikkim does not have its own academic University as of now. The colleges of Sikkim are affiliated to the North Bengal University (NBU) located in the district of Darjeeling, West Bengal. However, in this connection the task force, constituted by the Government of Sikkim, has submitted a report on the subject in January 2003. The Sikkim University Bill 2003 was introduced and passed unanimously in Sikkim Legislative Assembly on 26th of February 2003 so as to establish academic and research intensive University in the state of Sikkim. The Governor of Sikkim has already given assent to the bill. The Sikkim University Act is now presently being published by Law Department of the state. The two colleges in the state are Namchi College, located in Namchi, South District and Tadong Gangtok College, located in Tadong, East District. They are the conventional colleges and impart education at undergraduate level in social sciences, natural sciences, commerce and language & literature both at honours and pass levels. For the post graduation in the above streams the nearest university that Sikkimese students have to go to is the NBU located in siliguri of Darjeeling district, West Bengal.

The state of Sikkim, realizing the importance of modern technology and the advent of computer age has been striving to equip the Sikkimese students with adequate knowledge and exposure in the area. In this regard the state has been taking initiative to meet the technical and information challenges and has been giving high priority in its policy statements on industry and information technology and education.

As early as in 1998 Sikkim Manipal University was established in the state with two technical colleges under it. Sikkim Manipal Institute of Technology (SMIT) located in Majhitar imparts diploma, under graduate and postgraduate courses in various fields of engineering and information technology. The Sikkim Manipal Institute of Medical Sciences (SMIMS) located in Tadong, Gangtok offers various medical courses including MBBS. Besides, it also serves as a referral hospital to the people of Sikkim.

It is also that the Industrial Training Institute (ITI) at Singtam established in 1976 has been training Sikkimese on various technical courses like draughtsman, electronics mechanical, electrician, fitter, mechanic (motor vehicle), welder, and plumber at the diploma level. However, the department of education is not happy with the response of the Sikkimese. In spite of the very nominal fees for the courses in the ITI the Sikkimese prefer to go for the conventional degree colleges rather than acquiring technical skills from this institute. As a result majority of the trainees in the ITI has been the non-Sikkimese over the years. The growing unemployment in the state makes it imperative that the Sikkimese youth need to take the training in technical skills of the type provided in the ITIs and Polytechnics. For that Sikkimese students and parents need to change their mindset and the government need to encourage the locals to take up such courses.

Further, there are two polytechnics established under World Bank funded Third Technician Education Project. Two institutes namely, Advanced Technical Training Institute located at Bardang (ATTC) and Centre for Computer and Communication at Chisopani (CCCT) offer diploma and post diploma courses in various technical fields (Box). The All India Council for Technical Education (AICTE) has approved the courses offered by these institutes.

The state government intends these World Bank funded Institutes to be model institutes and ‘Centre of Excellence’ with the latest technologies and facilities. Their establishment is designed to address the need for employable skills to be imbibed among the youth of the state. It is hoped this noble venture of the state would address the development constraints of the state and also aid the technically qualified youths to seek potential employment outside the state.

Computer Education in Govt. Schools of SikkimThe state government of Sikkim has taken a conscious decision to embark on a computer literacy programme in the schools of the state. The ultimate objective is the computerization of all schools in the state at secondary and senior secondary levels. The programme has been taken in three phases. In the first phase the state has set a target of introducing computer education in 29 senior secondary schools (which was already achieved in 2002-03) and there after in the second phase and the third phase all the remaining 7 senior secondary and 80 secondary schools are proposed to be covered under the programme.

Smart School Concept

To create the prospective labour forces of Sikkim suitable, useful and in consonance with the new age, the state has decided to start ‘Smart Schools’ in the state. The concept of smart school is based on modern curriculum including science and technology, computer and environmental subjects. It would change the conventional educational pattern and bring about a more holistic educational approach in the state.

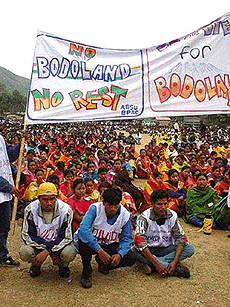

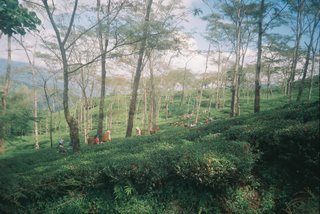

Investment in Education and employment prospectsMention should be made at this point that Sikkim has a comparative advantage with regard to its climatic set up, geographical location and overall environmental quality. This is to say; Sikkim offers good opportunities for opening up residential public schools- private, semi-private and government with strong emphasis on the quality of education and modern innovations. This was exactly the situation in the hills of Darjeeling which used to provide the best quality schools, private and those run by the christen missionaries, in the entire Eastern Himalayan Region. Thousands of students from the whole of South Asia and other places used to study in the various schools of Darjeeling hills. However, due to the ethnic riot and the subsequent political disturbances in the region the quality of education in the schools have been disrupted and their appeal declined in the last two decades.

Sikkim can grasp this opportunity under its fold as it has similar pristine locations and climatic setup for the boarding schools. Already, missionary schools like St Xavier in Pakyong and Holy Cross in Gangtok have been contributing vehemently in this regard and have made their marks in the state’s education. The state can encourage the private sectors to invest in the state in this regard. This will not only improve the standards of Sikkimese students but also contribute to the employment generations, which is so essential in the state of Sikkim in present times.

The farsighted leadership in the state of Sikkim in the last few years particularly in the last decade of the last century has resulted in the establishment of many professional education centres including engineering, medicine, and information technology. Further, the global outlook of the state in recent years has attracted the attention of the international agencies like World Bank, UNDP, Aus-Aid etc who have already started investing for the cause of sustainable development, in various development sectors including education, of this emerging state.

The need of the hour is to sustain the pace at which the state is moving ahead in the field of education. Private schools need to be encouraged strongly without discouraging the government schools. The state needs to update the quality of education and teachers in government schools through periodic monitoring and training. The Non Governmental Organizations would be of utmost help in this regard. The professional education like engineering, medicines and information technology need to be brought in the line of IITs and AIIMS. Further, other important prospective development subjects like rural, urban and regional development planning & management, hotel and tourism management, business management, architecture etc should found places in the state of Sikkim with massive private investments in the next couple of years. And the conventional academic subjects like chemistry, physics, mathematics, accountancy and social sciences disciplines need to be strengthened. The need for efficient development and business managers will increase with the growing complexity and size of Sikkimese economy and society, industrial establishments and other tertiary sector activities like tourism and trade.

Education Goals of the Sikkim GovernmentIn compliance with the state government policy and in consonance with the national objectives as enshrined in the New Education Policy of 1986 (NEP) and Programme of action 1992 (POA), the Government of Sikkim’s Education Goals may be mentioned as follows-

·100 percent enrolment of children at the primary level by 2007,

·100 percent completion of primary teachers training,

·Increase of literacy rates to 75 percent by 2007 and 80 percent by 2012,

·Universalisation of education at all levels,

·Implementation of Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan (SSA) in a time bound manner,

·Launching of non formal education programmes such as Education Guarantee Schemes (EGS) and Alternative Innovation Education (AIE) under the aegis of SSA,

·Achieving retention of students in the Education System and maximizing levels of learning,

·Consolidation of Socially Useful Productive Work (SUPW), Work Experience, Moral Science and Value Education,

·Diversion of a minimum of 20 percent student at the secondary level towards vocational streams as per the recommendations of the Kothari Commission,

·Implementation of a Comprehensive Technical Education Programme,

·Consolidation of Craftsmen Training in the state,

·Reduction in the rate of school dropouts.

**Note: This write up has been extracted from the draft chapter on Education,“Sikkim Development Report 2004”, prepared by this writer under the guidance of Prof. Mahendra P. Lama. The project was funded by the Planning commission of India and coordinated by NIPFP, New Delhi.