Autonomous Development Councils across Indian Himalayas

The last two decades of the 20th century witnessed the creation of three Autonomous Development Councils (ADCs) within Indian Federation. They are Darjeeling Gorkha Hill Council (1988), Ladakh Autonomous Development Council (1995) and Bodo Autonomous Development Council (1993). It restructured and decentralized our conventional system of federation, which normally consists of the Union and the Federated Units (states). ADCs are basically district level councils created within a district and under the presence of traditional district level administration. They are mainly responsible for taking care of development activities within their functional jurisdiction while the district administration, as a representative of the state, looks after the general administration of the district. ADCs in India have been formed taking into account the factors like geographical isolation, distinct regional identity and some special problems different from that of mainstream India. They are to be more precise, the result of long ethnic struggle to regain a measure of political autonomy from the ruling state. The premise on which they have been created lies in the fact that decentralization of power would give a boost to the developmental activities and meet the aspiration of the people. The focal aim behind the creation of ADCs is, thus, the socio-economic and cultural advancement of the local people within the established council.

Ladakh Autonomous Development Council

Ladakh is a region located in the Trans-Himalayas and is geographically isolated from rest of the state of Jammu and Kashmir. Consequently, the people of the area have had a distinct regional identity in terms of ethnic composition, religion and linguistics from those of the other areas of the state. The people of Ladakh have for a long time demanded effective local institutional arrangement that can help promote and accelerate the pace of development and equitable all round growth and development having regard to its unique geo-climatic and locational conditions and stimulate fullest participation of the local community in the decision making process. The demand was to regain a measure of autonomy from the state of Jammu and Kashmir.

The history of the struggle can be traced to the loss of independence of Ladakh in the 1830s and more immediately to the 1930s and particularly after the accession of the state to newly independent India. Initially, the struggle had been intermittent and thus failed to make much progress. It was however, resumed in 1989 when the Ladakh Buddhist Association launched a violent communal agitation. Finally, negotiations with the central and state government were followed and a compromise was reached upon in 1995 based on the Darjeeling Gorkha Hill Council model. To this effect Ladakh Autonomous Hill Development Council Act, 1995 was enacted and thus LAHDC was formed.

The creation of LAHDC has not been able to address the aspirations and needs of the Ladakhis over the years. Buddhists, as they are called in Ladakh, still feel that they suffer discrimination in every field of development and are thus treated as second-class citizens. There are voices to resume an agitation for total secession from the state, which was the original demand: ‘Free Ladakh from Kashmir’.

Bodo Autonomous Development Council

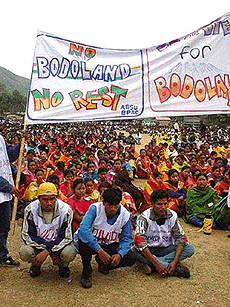

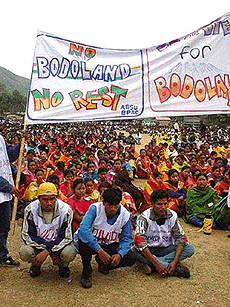

The Bodo problem is multidimensional in nature. Bodo, basically, refers to a tribal group residing in the state of Assam and often regarded as autochthonous in the region. The movement initially started with a cry for identity supposed to be endangered by the myopic outlook of the then chauvinistic groups ruling Assam. Subsequently the question of ascertaining political rights and constitutional safeguards came up. Moreover, there arose protests against the exploitation and deprivation of the common man by the ruling clique and the upper class. Later, the need for protection and preservation of language, literature, culture and tradition of the Bodos emerged which became the most emotional issue for the community in the 1960s. The illegal immigration in the state from the surrounding regions amplified the situation.

Today, the right of self-determination has been a single agenda among the Bodos – with various interpretations, from a mere political autonomy to complete freedom, that is, a separate nation. However, the common goal of all Bodo Organizations is the creation of a separate state of Bodoland. The Bodo movement took violent turn since 1980 when a vigorous mass movement started in the region. The movement came to an end in 1993 with the signing of the Bodo Accord. This treaty led to the creation of the Bodoland Autonomous Council. The Bodo Accord and Bodo Council could not keep pace with the aspirations and requirements of the Bodos. Today the Bodo movement has been revived.

Darjeeling Gorkha Hill Council

Darjeeling Himalaya, presently northernmost district of West Bengal, passed through abnormal history. An integral part of the Kingdom of Sikkim till 1706, it was ruled by Bhutan, Nepal and British India in the subsequent years before it was permanently taken over by the Government of India after 1947. As a result, the region evolved as a multi-ethnic, multi-cultural and multi-lingual area.

The social groups with diverse history and corresponding needs and demands were not satisfied with the mainstream development framework and started struggling for the separate politico-administrative identity. Evidences available in this context highlight that people living in the region had to pass through difficult phases in the process of development and importantly never formed the part of the mainstream development process. The district saw ethnic insurgencies with diverse characteristics and demands for a long period of time starting since 1907. Ultimately, Darjeeling Gorkha Hill Council was formed under the State Act in July 1988.

The decade of 1990s saw radical changes on the political scenario of Darjeeling. The DGHC consisted of councilors elected by the people of Darjeeling. This body was granted autonomy to function as an independent body. However, with the passage of time, over-confidence set in among the councilors of Darjeeling. Easy win in elections ensured the councillors' lethargy to work. There was frequent funds mismanagement. Funds earmarked for development projects were diverted to pay for overheads. Over the years, the situation gained momentum. It is alleged, in spite of the formation of DGHC, Darjeeling is still a neglected region. Development work has failed to yield desired results.

More recently, there had been voices like including the whole of Darjeeling Hills under Sixth Schedule or Article 371 of the Indian Constitution. Local political forces were also talking of including the left over Siliguri subdivision of Darjeeling district and the Gorkha/Nepali dominated Dooars region of Jalpaiguri district within the preview of DGHC. Consequently, a new chapter to the history of Darjeeling hills was added on December 6, 2005 following a tripartite agreement between the DGHC, the West Bengal government, and the Government of India. It was formally agreed upon to include Darjeeling hills in the Sixth Schedule of the Constitution with two more mauzas to be the part of the updated Council. The objective of this agreement is to replace the existing Darjeeling Gorkha Hills Council to be known as Gorkha Hill Council, Darjeeling, and to fulfill economic, educational and linguistic aspirations and the preservation of land rights, socio-cultural and ethnic identity of the hill people and to speed up the infrastructure development in the hill areas.

The extension of Sixth Schedule to Darjeeling Hills is not without controversies. There is hardly any difference between what the Council was before and what it is now except that it got constitutional recognition. The council already had a considerable amount of autonomy with respect to administrative and development matters. There will only be some minor changes here and there and revision of electoral representation in the updated Council. Further, as earlier, the offices of the District Magistrate and Superintendent of Police will be outside the control and direction of the new Council.

Questioning the relevance of ADCs

The complexities in the functioning of ADCs and prevailing socio-economic and political situations therein compel us to question the very existence of Autonomous Development Councils (ADCs) in the country. Some of the pertinent queries that we would like to be clarified in this connection can be listed as:

·What is the political status of ADCs?

·Are ADCs appropriate development units?

·What is the planning and development status of ADC areas within the Indian Federation?

·Are ADCs suitable answers to the geographical, historical, socio-cultural and political constraints of the people?

·Who is being empowered here, on what basis and to what extent?

It is important to understand that mere institutional and legal empowerment of the local communities does not address in itself issues of social justice and inequality and certainly does not lead naturally or necessarily to better policies. At the same time we also need to know that devolution and decentralization are an indispensable component of any attempt to move towards social justice and sustainability. The challenge ahead is to re-conceptualize the very concept of community representation and the institutional arrangements that we often envision in the context of their relevance to the regions and the people therein so that inter-regional as well as intra-regional disparities/conflicts are reduced and sustainable development is attained. Besides, scientific allocations of resources and the respective functions in this regard need also to be worked out systematically.

**Shorter version of this article was published in The Statesman, April 5, 2006.

The last two decades of the 20th century witnessed the creation of three Autonomous Development Councils (ADCs) within Indian Federation. They are Darjeeling Gorkha Hill Council (1988), Ladakh Autonomous Development Council (1995) and Bodo Autonomous Development Council (1993). It restructured and decentralized our conventional system of federation, which normally consists of the Union and the Federated Units (states). ADCs are basically district level councils created within a district and under the presence of traditional district level administration. They are mainly responsible for taking care of development activities within their functional jurisdiction while the district administration, as a representative of the state, looks after the general administration of the district. ADCs in India have been formed taking into account the factors like geographical isolation, distinct regional identity and some special problems different from that of mainstream India. They are to be more precise, the result of long ethnic struggle to regain a measure of political autonomy from the ruling state. The premise on which they have been created lies in the fact that decentralization of power would give a boost to the developmental activities and meet the aspiration of the people. The focal aim behind the creation of ADCs is, thus, the socio-economic and cultural advancement of the local people within the established council.

Ladakh Autonomous Development Council

Ladakh is a region located in the Trans-Himalayas and is geographically isolated from rest of the state of Jammu and Kashmir. Consequently, the people of the area have had a distinct regional identity in terms of ethnic composition, religion and linguistics from those of the other areas of the state. The people of Ladakh have for a long time demanded effective local institutional arrangement that can help promote and accelerate the pace of development and equitable all round growth and development having regard to its unique geo-climatic and locational conditions and stimulate fullest participation of the local community in the decision making process. The demand was to regain a measure of autonomy from the state of Jammu and Kashmir.

The history of the struggle can be traced to the loss of independence of Ladakh in the 1830s and more immediately to the 1930s and particularly after the accession of the state to newly independent India. Initially, the struggle had been intermittent and thus failed to make much progress. It was however, resumed in 1989 when the Ladakh Buddhist Association launched a violent communal agitation. Finally, negotiations with the central and state government were followed and a compromise was reached upon in 1995 based on the Darjeeling Gorkha Hill Council model. To this effect Ladakh Autonomous Hill Development Council Act, 1995 was enacted and thus LAHDC was formed.

The creation of LAHDC has not been able to address the aspirations and needs of the Ladakhis over the years. Buddhists, as they are called in Ladakh, still feel that they suffer discrimination in every field of development and are thus treated as second-class citizens. There are voices to resume an agitation for total secession from the state, which was the original demand: ‘Free Ladakh from Kashmir’.

Bodo Autonomous Development Council

The Bodo problem is multidimensional in nature. Bodo, basically, refers to a tribal group residing in the state of Assam and often regarded as autochthonous in the region. The movement initially started with a cry for identity supposed to be endangered by the myopic outlook of the then chauvinistic groups ruling Assam. Subsequently the question of ascertaining political rights and constitutional safeguards came up. Moreover, there arose protests against the exploitation and deprivation of the common man by the ruling clique and the upper class. Later, the need for protection and preservation of language, literature, culture and tradition of the Bodos emerged which became the most emotional issue for the community in the 1960s. The illegal immigration in the state from the surrounding regions amplified the situation.

Today, the right of self-determination has been a single agenda among the Bodos – with various interpretations, from a mere political autonomy to complete freedom, that is, a separate nation. However, the common goal of all Bodo Organizations is the creation of a separate state of Bodoland. The Bodo movement took violent turn since 1980 when a vigorous mass movement started in the region. The movement came to an end in 1993 with the signing of the Bodo Accord. This treaty led to the creation of the Bodoland Autonomous Council. The Bodo Accord and Bodo Council could not keep pace with the aspirations and requirements of the Bodos. Today the Bodo movement has been revived.

Darjeeling Gorkha Hill Council

Darjeeling Himalaya, presently northernmost district of West Bengal, passed through abnormal history. An integral part of the Kingdom of Sikkim till 1706, it was ruled by Bhutan, Nepal and British India in the subsequent years before it was permanently taken over by the Government of India after 1947. As a result, the region evolved as a multi-ethnic, multi-cultural and multi-lingual area.

The social groups with diverse history and corresponding needs and demands were not satisfied with the mainstream development framework and started struggling for the separate politico-administrative identity. Evidences available in this context highlight that people living in the region had to pass through difficult phases in the process of development and importantly never formed the part of the mainstream development process. The district saw ethnic insurgencies with diverse characteristics and demands for a long period of time starting since 1907. Ultimately, Darjeeling Gorkha Hill Council was formed under the State Act in July 1988.

The decade of 1990s saw radical changes on the political scenario of Darjeeling. The DGHC consisted of councilors elected by the people of Darjeeling. This body was granted autonomy to function as an independent body. However, with the passage of time, over-confidence set in among the councilors of Darjeeling. Easy win in elections ensured the councillors' lethargy to work. There was frequent funds mismanagement. Funds earmarked for development projects were diverted to pay for overheads. Over the years, the situation gained momentum. It is alleged, in spite of the formation of DGHC, Darjeeling is still a neglected region. Development work has failed to yield desired results.

More recently, there had been voices like including the whole of Darjeeling Hills under Sixth Schedule or Article 371 of the Indian Constitution. Local political forces were also talking of including the left over Siliguri subdivision of Darjeeling district and the Gorkha/Nepali dominated Dooars region of Jalpaiguri district within the preview of DGHC. Consequently, a new chapter to the history of Darjeeling hills was added on December 6, 2005 following a tripartite agreement between the DGHC, the West Bengal government, and the Government of India. It was formally agreed upon to include Darjeeling hills in the Sixth Schedule of the Constitution with two more mauzas to be the part of the updated Council. The objective of this agreement is to replace the existing Darjeeling Gorkha Hills Council to be known as Gorkha Hill Council, Darjeeling, and to fulfill economic, educational and linguistic aspirations and the preservation of land rights, socio-cultural and ethnic identity of the hill people and to speed up the infrastructure development in the hill areas.

The extension of Sixth Schedule to Darjeeling Hills is not without controversies. There is hardly any difference between what the Council was before and what it is now except that it got constitutional recognition. The council already had a considerable amount of autonomy with respect to administrative and development matters. There will only be some minor changes here and there and revision of electoral representation in the updated Council. Further, as earlier, the offices of the District Magistrate and Superintendent of Police will be outside the control and direction of the new Council.

Questioning the relevance of ADCs

The complexities in the functioning of ADCs and prevailing socio-economic and political situations therein compel us to question the very existence of Autonomous Development Councils (ADCs) in the country. Some of the pertinent queries that we would like to be clarified in this connection can be listed as:

·What is the political status of ADCs?

·Are ADCs appropriate development units?

·What is the planning and development status of ADC areas within the Indian Federation?

·Are ADCs suitable answers to the geographical, historical, socio-cultural and political constraints of the people?

·Who is being empowered here, on what basis and to what extent?

It is important to understand that mere institutional and legal empowerment of the local communities does not address in itself issues of social justice and inequality and certainly does not lead naturally or necessarily to better policies. At the same time we also need to know that devolution and decentralization are an indispensable component of any attempt to move towards social justice and sustainability. The challenge ahead is to re-conceptualize the very concept of community representation and the institutional arrangements that we often envision in the context of their relevance to the regions and the people therein so that inter-regional as well as intra-regional disparities/conflicts are reduced and sustainable development is attained. Besides, scientific allocations of resources and the respective functions in this regard need also to be worked out systematically.

**Shorter version of this article was published in The Statesman, April 5, 2006.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home